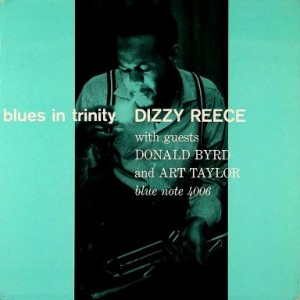

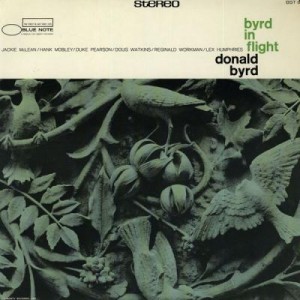

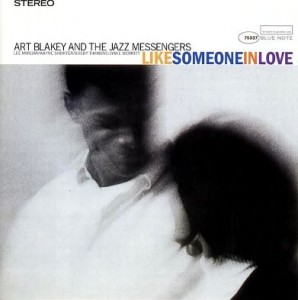

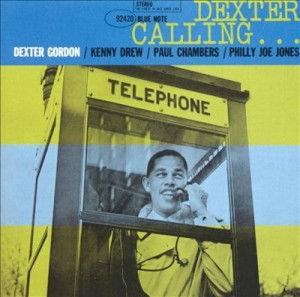

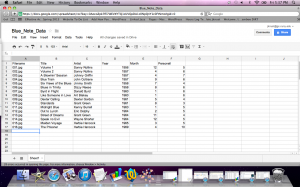

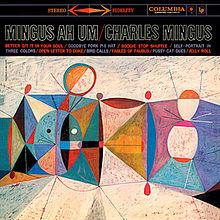

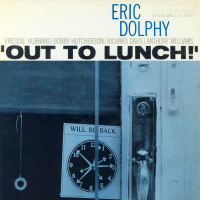

In my last post, I detailed a dry-run using a data set of sixteen images. I have now expanded the set to 42 Blue Note album covers, spanning from 1956 to 1969, with most of them from the late 1950s, to early 1960s. The work has been time-intensive, as, again, everything has been done pretty much by hand, from collecting the images and resizing them, to entering basic metadata into a spreadsheet. Far from making any earth-shaking discoveries at this point, my work thus far is best seen as a set of experiments–a work still in progress.

My rationale for undertaking this particular project is to examine the visual culture of jazz in a new way. Jazz itself, as a musical art form, has been studied and analyzed a great deal, as has its cultural impact. But the visual elements of jazz art, wholly apart from the music itself, seems to be an area ripe for new research. By examining jazz album covers as cultural icons in large data sets, some interesting features may present themselves.

Jazz can be seen as a pre-digital open access collaborative venture which foreshadows the new forms of scholarship emerging under the Digital Humanities banner. As an art form in which both individualism and collective improvisation flourish, jazz both reflects and influences the culture in which it resides.

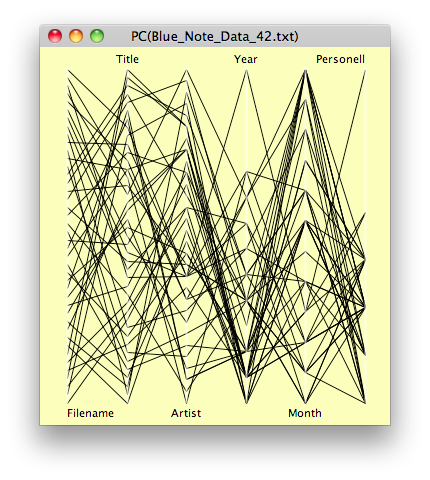

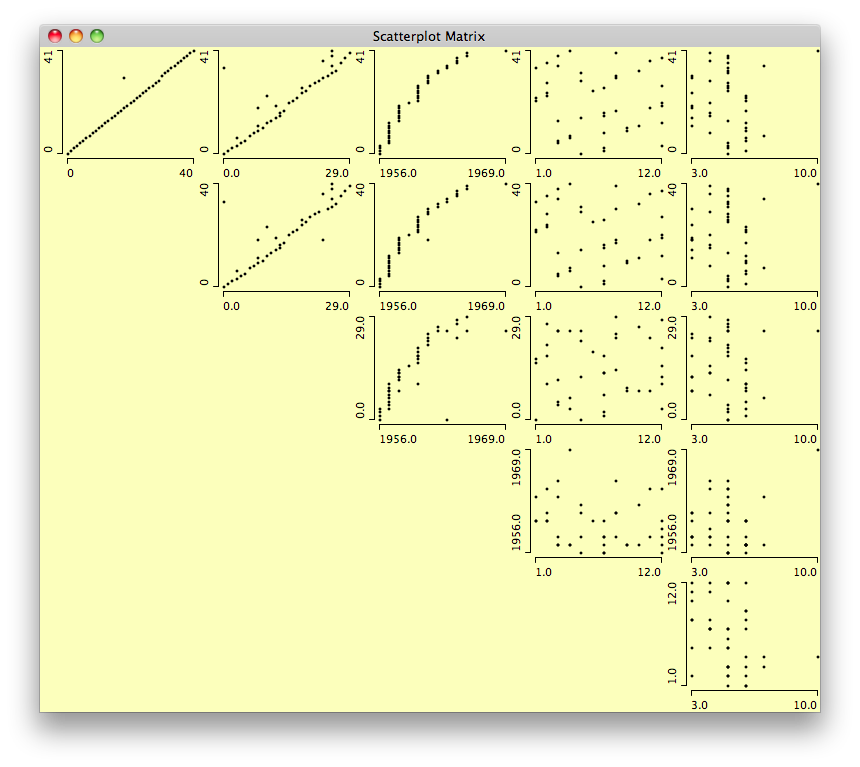

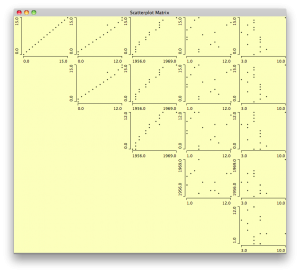

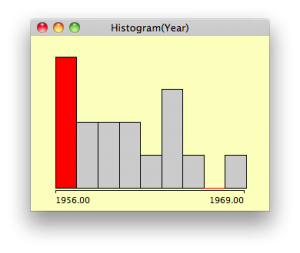

Let’s start with our expanded data set. Again, interesting to look at, but not much can be made of it.

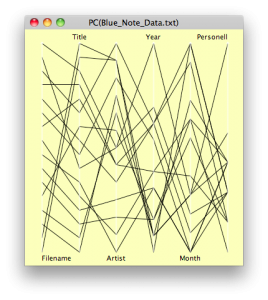

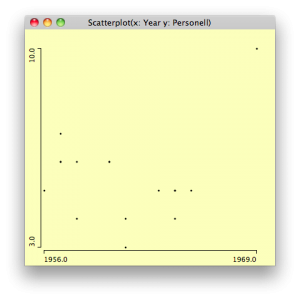

Here’s another view from Mondrian. Again, no surprises, but everything seems to work.

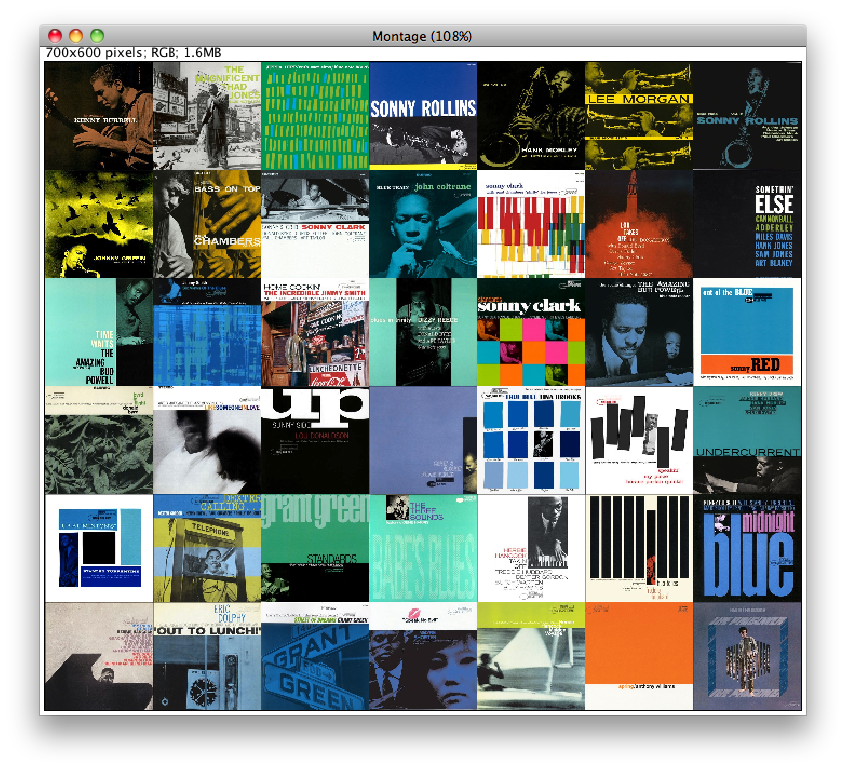

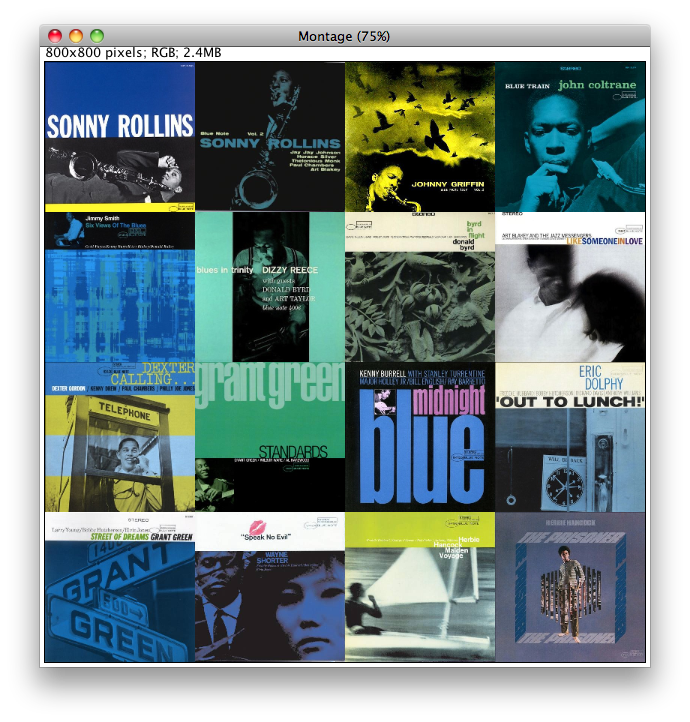

Though I made a great many plots in Mondrian, I feel compelled to move on to the images themselves. First off, this is the image montage, arranged chronologically:

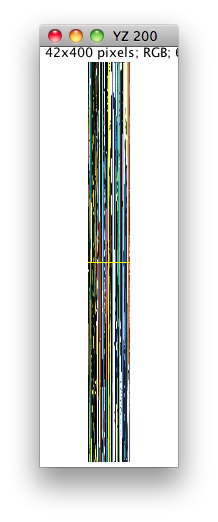

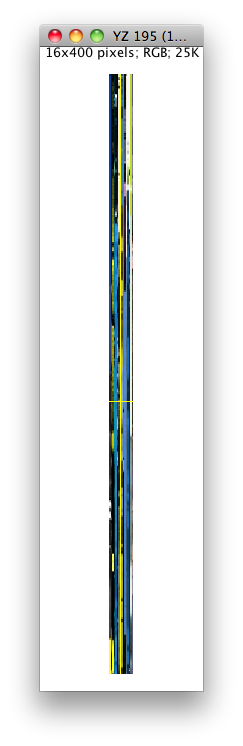

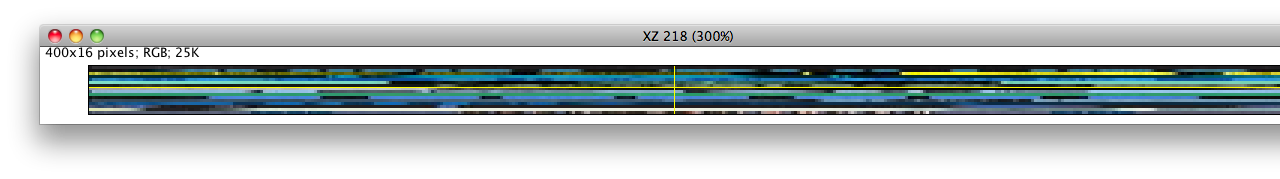

Next, we can view the image slices, both vertical and horizontal:

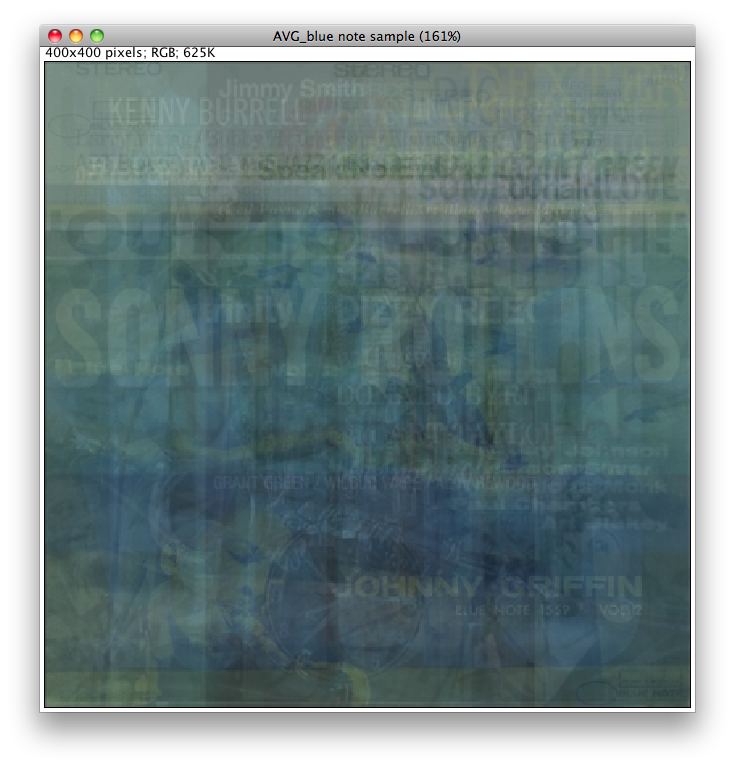

Next off, and really quite interesting, is all the images superimposed. This is based on the average intensity:

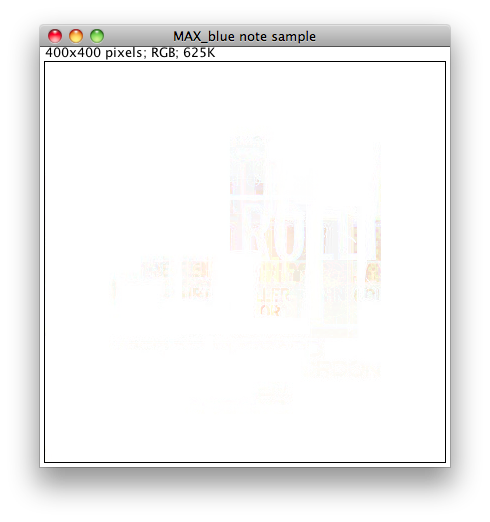

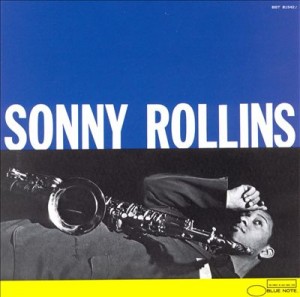

Next one is maximum intensity:

Somehow, Sonny Rollins shines through.

This next one I find quite beautiful:

It really stands alone as a work of art. Hank Mobley shows through here.

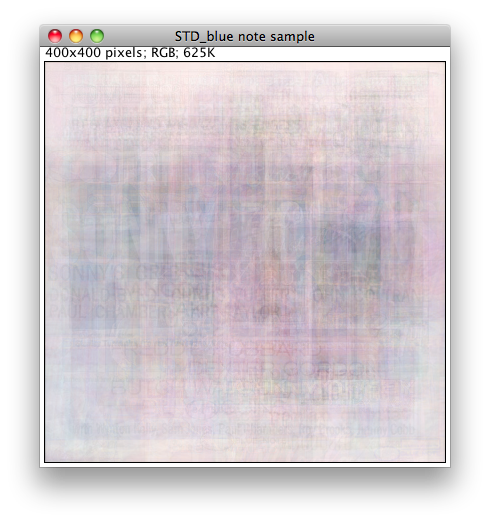

Standard deviation creates a pastel effect:

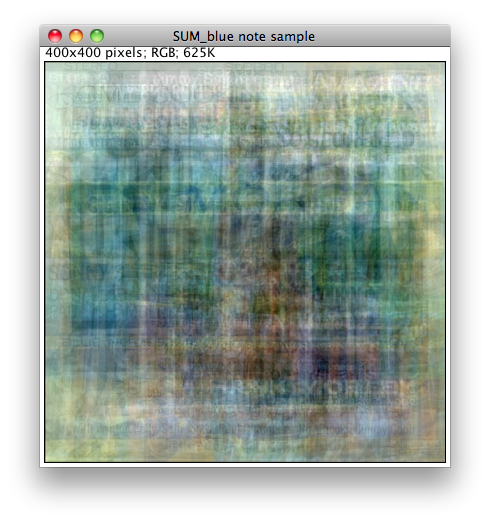

Median intensity creates a very interesting effect:

This is perhaps my favorite, as it shows the predominance of blues and greens throughout.

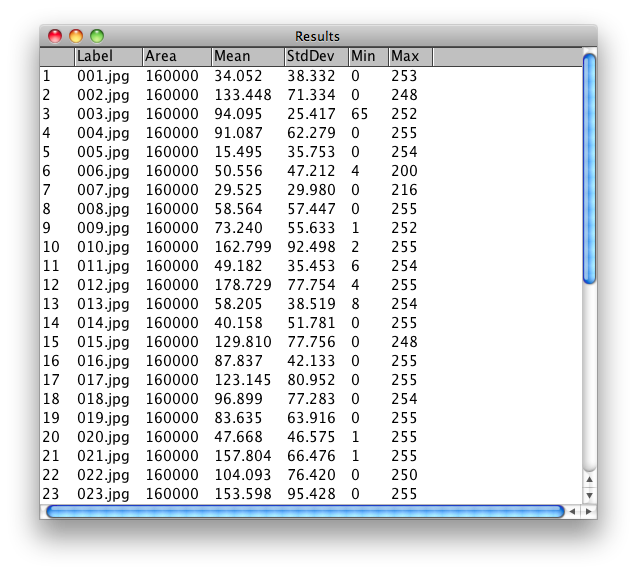

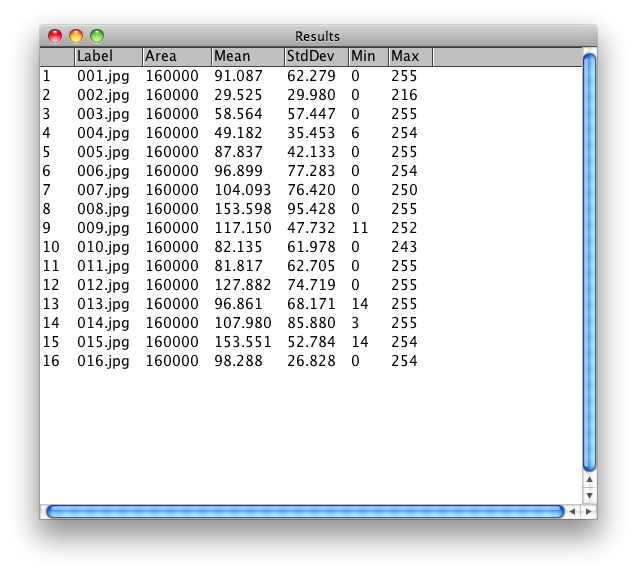

I got just to the point of measuring for different values, especially grey scale values:

As my work continues, I would like to be displaying the images based on these measurements, as well as hue, brightness, and other factors. As it stands, this is as far as I’ve been able to take it up to now. Ideally, I would also have a much larger image set to work with as well.

Ultimately, it would be interesting to compare sets of images from different jazz labels as well, such as Impulse, Columbia, and others, especially from this time period of late 1950s to mid 1960s.